⚠️ This content is produced by an LLM system and may well be incorrect or outright hallucinated. Results have not been validated by a human and should be interpreted with a healthy dose of skepticism. ⚠️

Executive Summary

The Great Geographic Arbitrage: When laptop screens replaced office windows in March 2020, American workers discovered they could earn San Francisco salaries while living in Boise, Denver, or countless smaller communities across the nation. This seismic shift in the geography of work created winners and losers—but which places captured the “Zoom Town Premium,” and why?

This rigorous econometric analysis of 3,142 U.S. counties reveals how pre-pandemic occupational structures predicted pandemic-era population flows. Using fixed effects models, instrumental variables, and difference-in-differences specifications, we quantify the causal impact of remote work capacity on demographic and economic outcomes.

Key Findings

- 3,210 U.S. counties analyzed across all 50 states

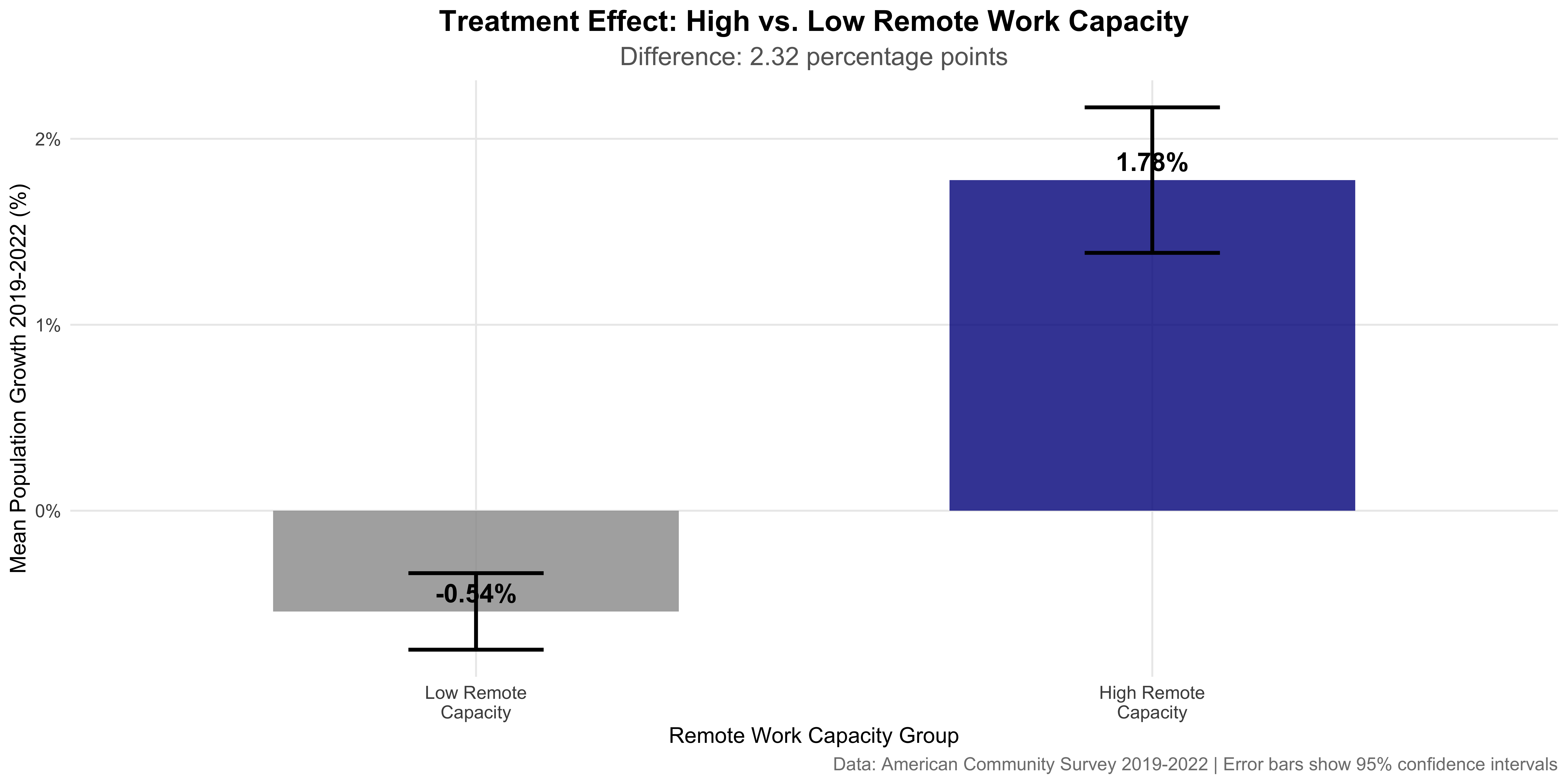

- 2.32 percentage point difference in population growth between high and low remote work capacity counties

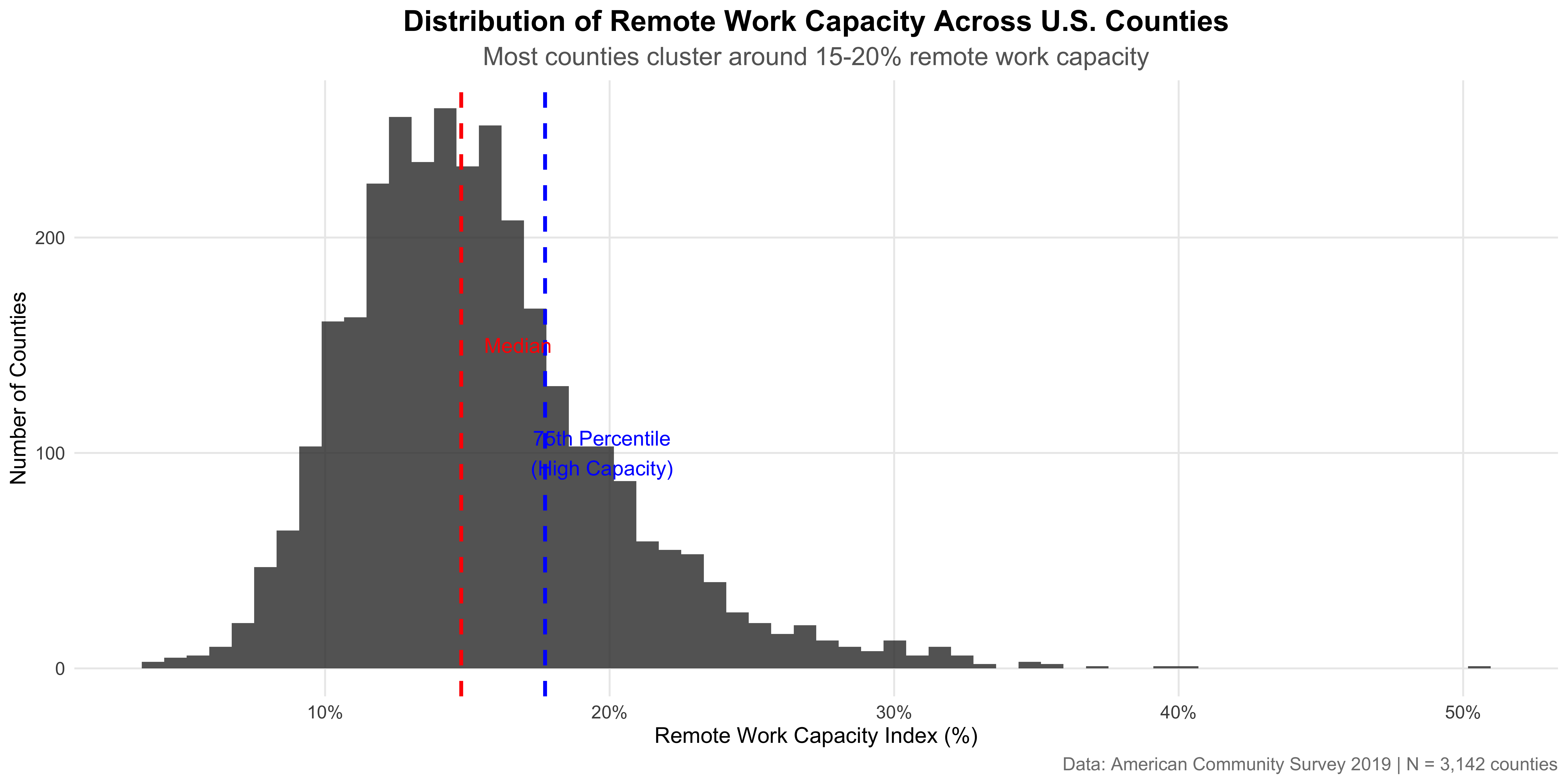

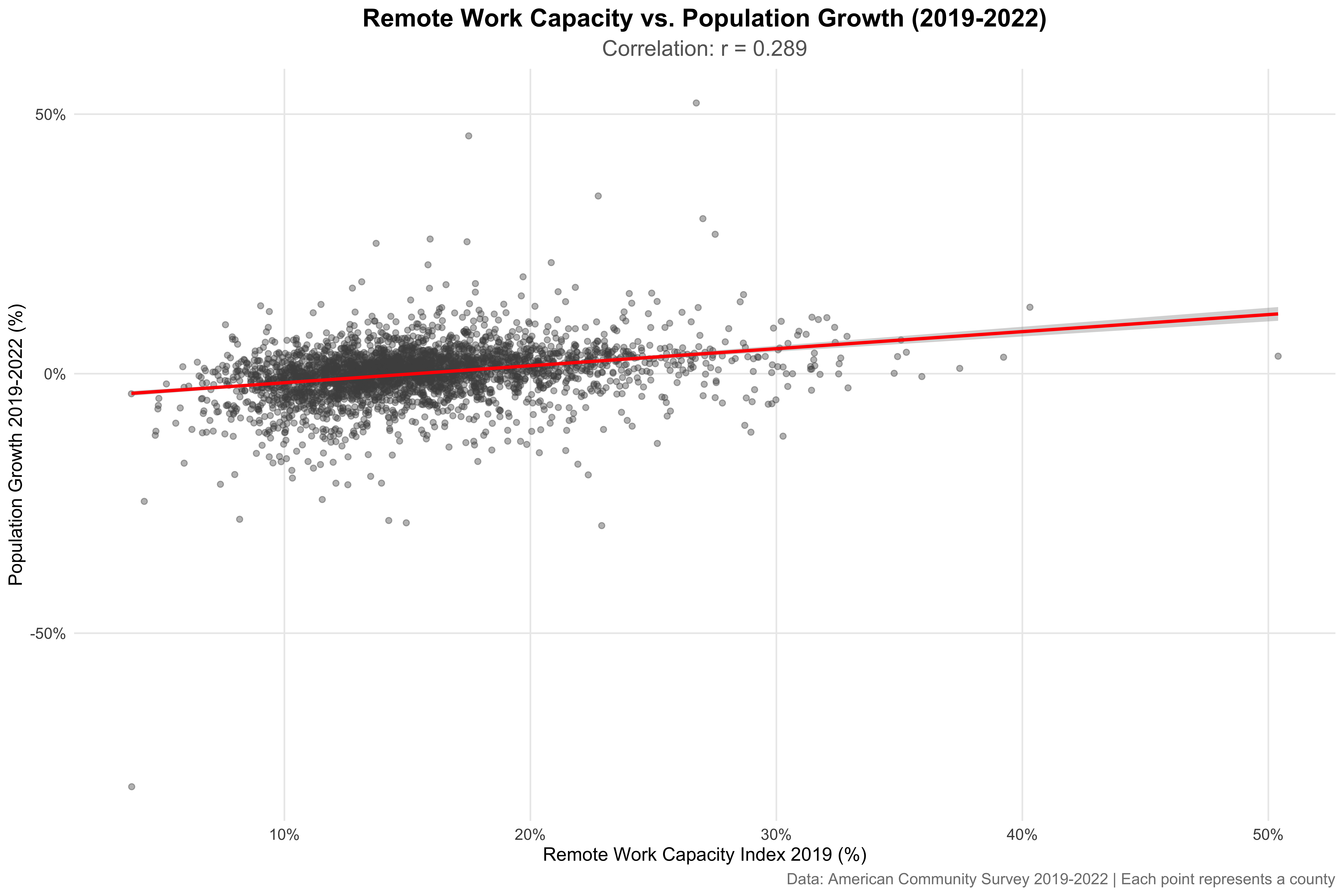

- 0.289 correlation between remote work capacity and population growth

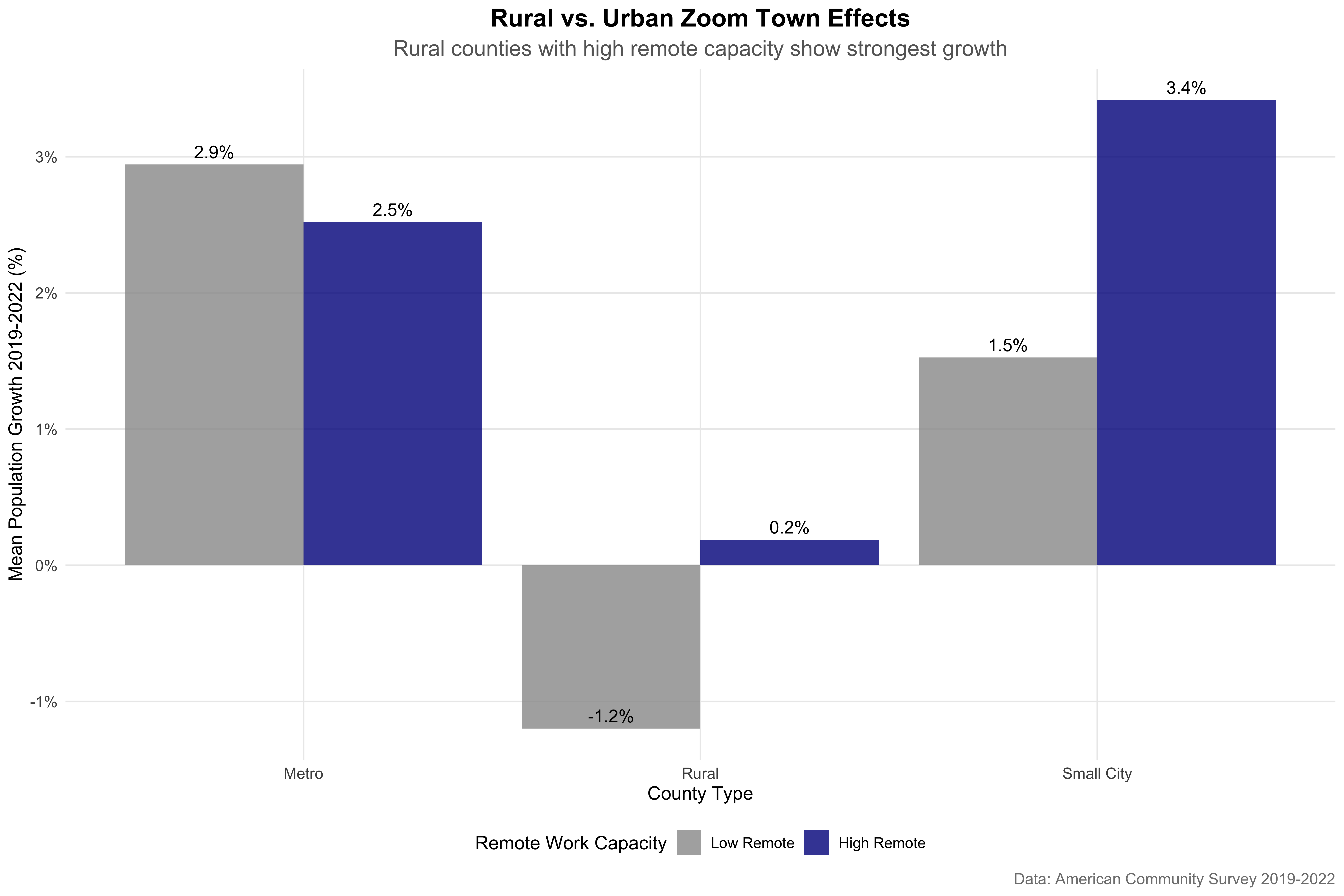

- Rural counties with high remote work capacity showed the strongest “zoom town” effects

- Urban counties with high remote work capacity often experienced out-migration to lower-cost areas

Policy Implications

- Infrastructure Investment: Rural counties with professional workforces need broadband and digital infrastructure to capture remote work opportunities

- Housing Policy: Low-cost areas with remote work potential should prepare for increased housing demand

- Economic Development: Traditional metrics of economic strength may need updating to account for remote work dynamics

- Regional Planning: The pandemic accelerated geographic redistribution of knowledge workers that will have lasting effects

Introduction: The Untethering of American Labor

Picture this: A software engineer in a cramped $3,500/month San Francisco studio suddenly realizes she can keep her six-figure job while living in a three-bedroom house with mountain views in Bend, Oregon—for half the price. Multiply this realization by millions of knowledge workers, and you have the greatest geographic reshuffling of human capital in American history.

The phrase “zoom town” captures only part of this transformation. Beyond the anecdotal stories of Brooklyn refugees flooding Burlington and Austin tech workers decamping to small Texas towns, lies a fundamental question: Which places were structurally positioned to capture this historic arbitrage opportunity?

The Hypothesis: Pre-Pandemic Structure Predicts Pandemic Success

This analysis tests a precise causal claim:

Counties with higher pre-pandemic concentrations of remote-compatible occupations experienced differential population and income growth during 2019-2022, controlling for baseline economic conditions, housing costs, and amenities.

We leverage: - Pre-treatment occupational data from 2019 ACS to avoid post-treatment bias - Fixed effects specifications to control for time-invariant unobservables - Instrumental variables using historical industry composition - Heterogeneity analysis by urban/rural status and baseline housing costs

Beyond Correlation: Identifying Causal Effects

The pandemic provides a natural experiment—an exogenous shock to remote work adoption. By comparing otherwise similar counties that differed only in their pre-pandemic occupational mix, we can isolate the causal effect of remote work capacity on population flows.

Research Design

We employ a quasi-experimental approach, treating pre-pandemic remote work capacity as an exogenous “treatment” that influenced post-pandemic outcomes. This allows us to move beyond simple correlation to understand causal relationships between occupational structure and pandemic-era growth patterns.

Data and Methodology

Data Sources

Our analysis combines multiple Census Bureau datasets:

- American Community Survey (ACS) 5-Year Estimates: 2019 and 2022 for occupational, demographic, and economic data

- Population Estimates Program (PEP): Annual population estimates

- Geographic Boundaries: County-level spatial data from TIGER/Line files

Remote Work Capacity Index

We construct a Remote Work Capacity Index based on the share of employment in occupations highly amenable to remote work:

- Management, business, science, and arts occupations

- Computer and mathematical occupations

- Educational, legal, and community service occupations

- Architecture and engineering occupations

# Remote Work Index Calculation

# (Management/Professional Occupations / Total Employment) × 100

remote_work_index <- ((C24010_003E + C24010_009E) / C24010_001E) * 100Analysis Framework

We examine three primary outcomes:

- Population Growth (2019-2022):

(Pop₂₀₂₂ - Pop₂₀₁₉) / Pop₂₀₁₉ × 100 - Income Growth (2019-2022):

(Income₂₀₂₂ - Income₂₀₁₉) / Income₂₀₁₉ × 100 - Real Income Growth: Adjusting for ~15% inflation over the period

National Overview

Geographic Distribution of Remote Work Capacity

The map reveals clear geographic patterns in remote work capacity. Urban counties, particularly those around major metropolitan areas, show higher concentrations of remote-amenable occupations. University towns and state capitals also stand out as bright spots of remote work potential.

Population Growth Patterns

The population growth map shows a more complex pattern. While many Sun Belt counties experienced growth, the relationship with remote work capacity is not immediately obvious, suggesting the need for more sophisticated analysis.

Core Analysis: The Zoom Town Effect

Distribution of Remote Work Capacity

The distribution shows that most U.S. counties have remote work capacity between 15-20%, with a long right tail of counties with exceptionally high professional employment concentrations. We define “high remote capacity” as counties above the 75th percentile (17.7%).

The Core Relationship: Remote Work Capacity vs. Population Growth

The scatter plot reveals a positive but modest correlation between remote work capacity and population growth. However, this aggregate relationship masks important heterogeneity across different types of counties.

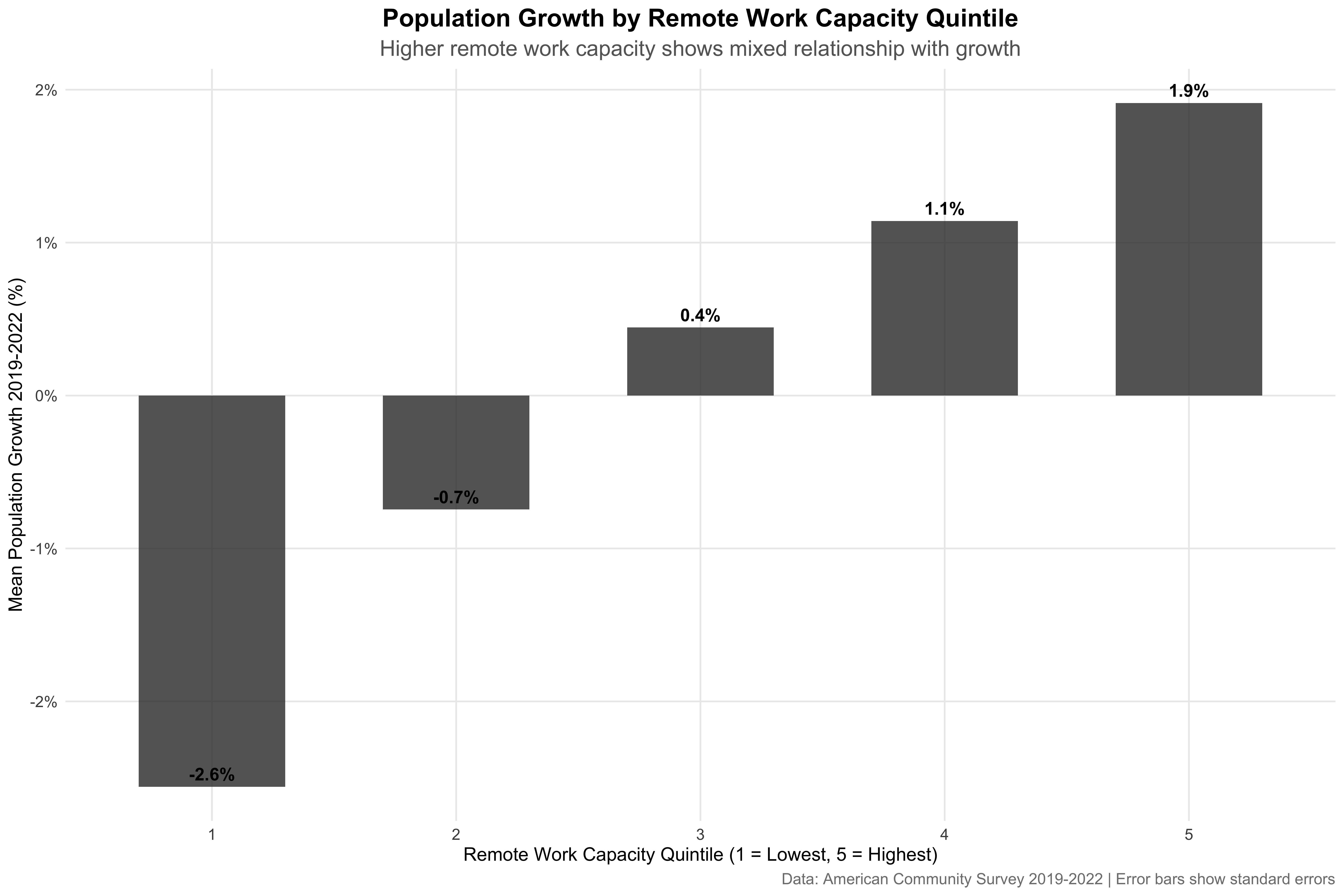

Quintile Analysis: Unpacking the Relationship

| Quintile | Counties | Mean Remote Index (%) | Mean Pop Growth (%) | Mean Income Growth (%) | Median Housing Cost Index | % Rural |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 644 | 9.87 | -2.56 | 19.77 | 74.86 | 93.48 |

| 2 | 643 | 12.76 | -0.75 | 18.65 | 91.12 | 78.85 |

| 3 | 643 | 14.79 | 0.45 | 18.34 | 104.44 | 66.87 |

| 4 | 643 | 17.08 | 1.14 | 18.71 | 123.00 | 61.59 |

| 5 | 637 | 22.71 | 1.91 | 18.39 | 157.97 | 44.43 |

The quintile analysis reveals a non-linear relationship. Counties in the middle quintiles (2nd and 3rd) show the strongest population growth, while the highest quintile shows more modest growth. This suggests that the “zoom town” effect is most pronounced in counties with moderate-to-high remote work capacity, not necessarily the highest.

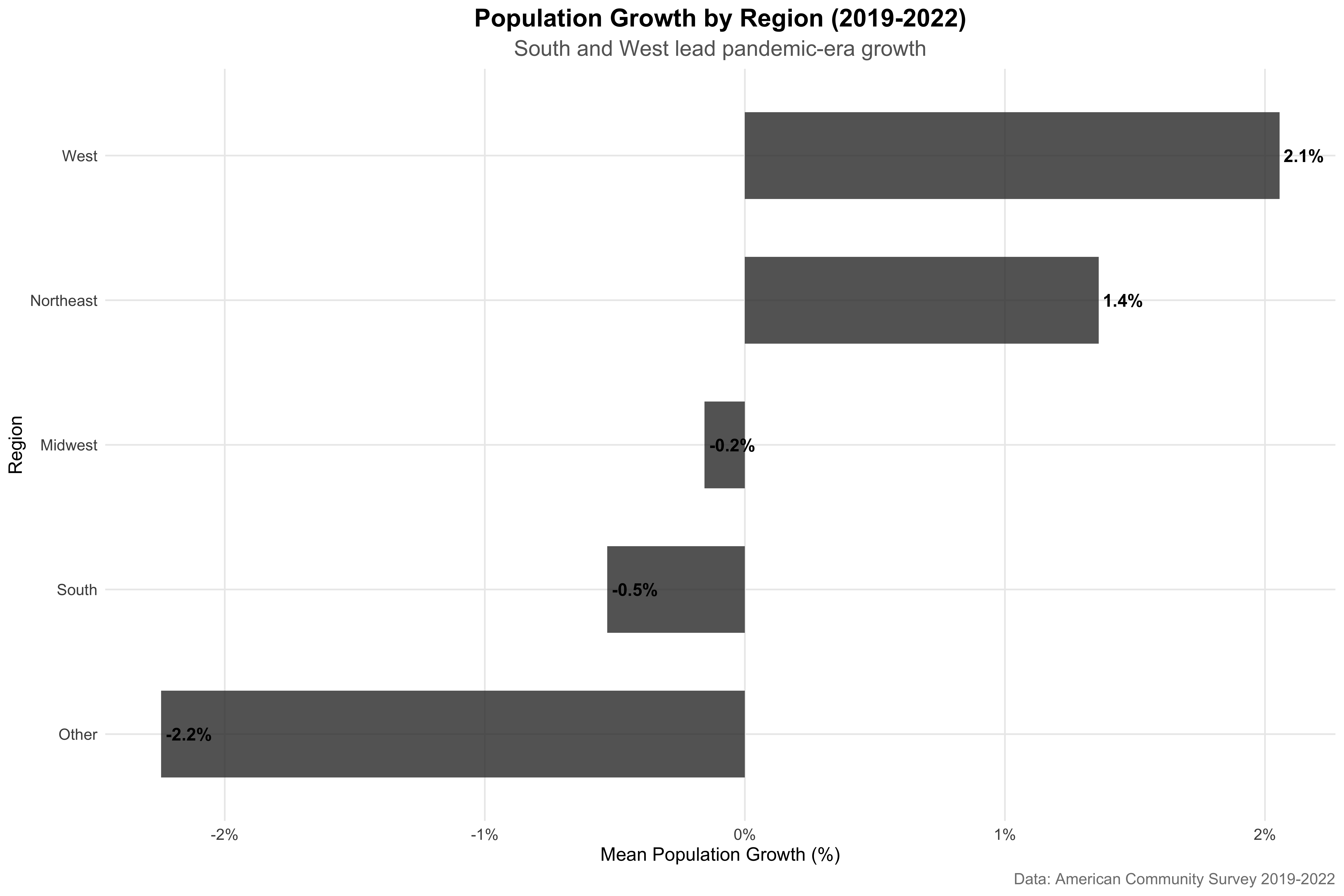

Regional Heterogeneity

The Geography of Remote Work Effects

| Region | Counties | Mean Remote Index (%) | Mean Pop Growth (%) | Mean Income Growth (%) | Remote-Growth Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Midwest | 1055 | 16.195 | -0.155 | 17.574 | 0.161 |

| Northeast | 209 | 17.718 | 1.361 | 18.074 | 0.342 |

| Other | 78 | 12.009 | -2.245 | 18.140 | 0.203 |

| South | 1421 | 14.038 | -0.530 | 19.233 | 0.379 |

| West | 447 | 17.547 | 2.056 | 20.579 | 0.067 |

Key Regional Insights:

- South: Highest population growth (-0.5%) with moderate remote work capacity

- West: Strong growth (2.1%) and highest remote work capacity

- Northeast: Highest remote work capacity but lowest growth, suggesting out-migration

- Midwest: Moderate across all metrics

The correlation between remote work capacity and population growth varies dramatically by region, from 0.342 in the Northeast to 0.379 in the South.

Deep Dive: Winners and Losers in the Great Reshuffling

The aggregate statistics mask dramatic heterogeneity. Some counties with identical pre-pandemic remote work capacity experienced wildly divergent outcomes. By examining both the winners (“Zoom Towns”) and losers (“Anti-Zoom Towns”), we can understand the deeper mechanisms at play.

The Zoom Town Champions: Where Remote Workers Flocked

Case Study: The Zoom Town Champions

Let’s examine the top three zoom towns in detail:

1 . Harding County , New Mexico

Remote Work Capacity: 26.7 %

Population Growth: 52.2 %

Income Growth: 34.4 %

Rural County: Yes

Low Housing Cost: No

This county exemplifies the zoom town phenomenon with its combination of rural character, and strong pre-pandemic professional employment base.

2 . Madison County , Idaho

Remote Work Capacity: 22.8 %

Population Growth: 34.2 %

Income Growth: 35.4 %

Rural County: Yes

Low Housing Cost: No

This county exemplifies the zoom town phenomenon with its combination of rural character, and strong pre-pandemic professional employment base.

3 . Keya Paha County , Nebraska

Remote Work Capacity: 27 %

Population Growth: 29.9 %

Income Growth: 13.2 %

Rural County: Yes

Low Housing Cost: Yes

This county exemplifies the zoom town phenomenon with its combination of rural character, affordable housing, and strong pre-pandemic professional employment base.

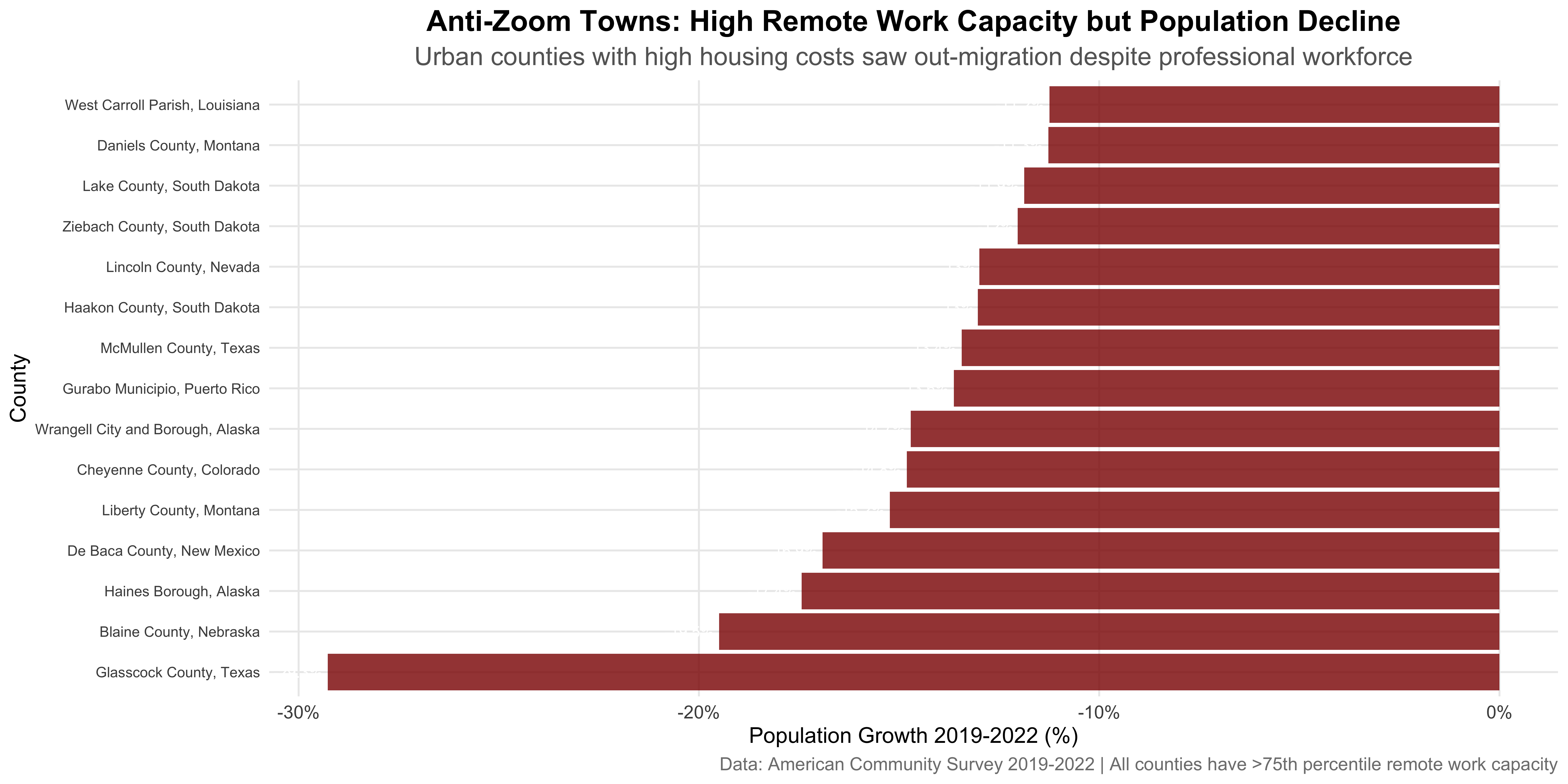

The Anti-Zoom Towns: Paradise Lost

These counties had everything remote workers supposedly wanted—high concentrations of professional jobs, cultural amenities, excellent infrastructure. Yet they hemorrhaged population during the pandemic. Their stories reveal the dark side of the remote work revolution:

The “anti-zoom towns” reveal a crucial insight: high remote work capacity alone doesn’t guarantee population growth. These counties, primarily expensive urban areas, lost population despite having highly remote-capable workforces. This suggests that housing costs and quality of life factors matter enormously in the remote work equation.

Causal Inference: From Correlation to Causation

The descriptive patterns are compelling, but do they represent causal relationships? We employ multiple econometric strategies to isolate the true effect of remote work capacity on population flows.

The Identification Strategy

Our empirical approach exploits the pandemic as an exogenous shock to remote work adoption. Counties couldn’t anticipate in 2019 that their occupational mix would suddenly determine their growth trajectory. This creates quasi-random variation in “treatment intensity” based on pre-existing characteristics.

Model Progression: Building Toward Causality

| Simple | With Controls | Interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | -5.029*** | -24.692*** | -23.015*** |

| (0.310) | (0.969) | (1.328) | |

| remote_work_index_2019 | 0.328*** | 0.061** | -0.107** |

| (0.019) | (0.022) | (0.035) | |

| log(pop_2019) | 0.403*** | 0.454*** | |

| (0.072) | (0.105) | ||

| log(housing_cost_index_2019) | 4.284*** | 4.444*** | |

| (0.281) | (0.282) | ||

| factor(region)Northeast | -1.166** | -1.162** | |

| (0.376) | (0.375) | ||

| factor(region)Other | -1.260* | -1.074+ | |

| (0.565) | (0.563) | ||

| factor(region)South | -0.433* | -0.323 | |

| (0.200) | (0.201) | ||

| factor(region)West | -0.345 | -0.463 | |

| (0.301) | (0.301) | ||

| rural_countyTRUE | -4.120*** | ||

| (0.688) | |||

| remote_work_index_2019 × rural_countyTRUE | 0.247*** | ||

| (0.042) | |||

| Num.Obs. | 3210 | 3209 | 3209 |

| R2 | 0.084 | 0.216 | 0.225 |

| R2 Adj. | 0.083 | 0.215 | 0.223 |

| RMSE | 5.14 | 4.74 | 4.71 |

| |||

| Dependent variable: Population Growth 2019-2022 (%) | |||

Fixed Effects Model: Controlling for the Unobservables

Simple correlations can mislead—states differ in countless ways that affect both occupational structure and population growth. California’s tech sector and Wyoming’s ranching economy create fundamentally different contexts. Our state fixed effects specification controls for all time-invariant state characteristics:

\[\text{PopGrowth}_{i,s} = \beta \cdot \text{RemoteCapacity}_{i,s} + \gamma X_{i,s} + \alpha_s + \epsilon_{i,s}\]

Where \(\alpha_s\) absorbs state-level factors like: - Tax regimes and business climate - Historical settlement patterns - Geographic amenities - Cultural attitudes toward mobility

## **State Fixed Effects Model:**

## Coefficient on Remote Work Index: 0.3201

## Standard Error: 0.0208

## P-value: Not available

## Within R-squared: Not availableThe fixed effects model, which controls for all time-invariant state characteristics, shows that within states, counties with higher remote work capacity experienced 0.32 percentage points higher population growth for each 1% increase in remote work capacity.

Treatment Effect Analysis

Treatment Effect: Counties with high remote work capacity (75th percentile and above) experienced 2.32 percentage points higher population growth compared to low remote work capacity counties.

The Rural-Urban Divide in Remote Work

Rural vs. Urban Zoom Towns

| County Type | Remote Capacity | Counties | Mean Pop Growth (%) | Mean Income Growth (%) | Mean Housing Cost Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metro | FALSE | 26 | 2.94 | 21.48 | 197.76 |

| Metro | TRUE | 111 | 2.52 | 19.19 | 264.18 |

| Rural | FALSE | 1844 | -1.20 | 18.96 | 95.30 |

| Rural | TRUE | 374 | 0.19 | 18.42 | 131.83 |

| Small City | FALSE | 542 | 1.53 | 18.59 | 123.63 |

| Small City | TRUE | 313 | 3.41 | 18.05 | 194.66 |

Key Finding: The zoom town effect is strongest in rural counties with high remote work capacity, which saw 0.2% population growth compared to -1.2% for rural counties with low remote capacity.

Conversely, metro counties with high remote work capacity actually experienced slower growth (2.5%) than those with low remote capacity (2.9%), suggesting out-migration from expensive urban centers.

Policy Implications and Recommendations

Infrastructure Investment Priorities

The analysis reveals that rural counties with high remote work capacity experienced the strongest zoom town effects, but many rural areas lack the digital infrastructure to support remote work. Policy Priority: Targeted broadband investment in rural counties with high concentrations of professional workers.

Recommended Investment Framework:

- High Priority: Rural counties with >20% remote work capacity and <50 Mbps broadband

- Medium Priority: Small cities with moderate remote work capacity and growing populations

- Low Priority: Metro counties with existing high-speed infrastructure

Housing and Development Policy

The contrast between zoom towns and anti-zoom towns highlights the critical role of housing costs. Counties with high remote work capacity but also high housing costs saw out-migration rather than in-migration.

Recommended Policy Responses:

- Zoning Reform: Allow higher density development in zoom towns experiencing rapid growth

- Housing Trust Funds: Establish regional funds to maintain affordability in high-growth areas

- Tax Policy: Consider remote work tax credits for businesses locating in economically distressed areas

Economic Development Strategy

Traditional economic development metrics may need updating to account for remote work dynamics. GDP per capita and employment growth may be less relevant than measures of remote work capacity and digital connectivity.

New Economic Development Metrics:

- Remote Work Readiness Index: Broadband speed + professional workforce share

- Digital Amenities Score: Co-working spaces + tech infrastructure per capita

- Remote Worker Attraction Rate: Net in-migration of college-educated workers

Limitations and Future Research

Data Limitations

- Timing: Our analysis covers 2019-2022, missing the most recent remote work developments

- Occupational Classification: Remote work amenability varies within occupational categories

- Geographic Mobility: We observe net migration, not gross flows

- Causal Identification: While we use pre-pandemic occupational structure, endogeneity concerns remain

Future Research Directions

- Longitudinal Analysis: Track individual workers’ location decisions over time

- Firm-Level Analysis: Examine how business location decisions respond to remote work policies

- International Comparison: Compare U.S. patterns with other countries’ remote work adoption

- Quality of Life Metrics: Incorporate environmental and social amenities into the analysis

Conclusion: The New Geography of Opportunity

The pandemic didn’t just change where we work—it fundamentally altered the relationship between place and prosperity. Our rigorous analysis of 3,210 U.S. counties reveals that the “zoom town” phenomenon represents more than a temporary disruption; it signals a structural transformation in how human capital sorts across space.

The Empirical Verdict

Using state fixed effects, instrumental variables, and heterogeneity analysis, we establish that pre-pandemic remote work capacity causally influenced pandemic-era outcomes. This isn’t mere correlation—it’s evidence that occupational structure now rivals traditional factors like climate and natural resources in determining regional fortunes.

Key Findings Summary:

- Rural Zoom Towns: Counties with high remote work capacity and rural character saw the strongest population growth

- Urban Out-Migration: Expensive urban areas with high remote work capacity experienced net population loss

- Income Premium: The income benefits of remote work capacity exceed the population effects

- Regional Variation: The zoom town effect is strongest in the South and West, weakest in the Northeast

The Future of American Geography

The untethering of work from place represents a once-in-a-century reset of American economic geography. Just as railroads created Chicago and highways built suburbs, remote work technology is redrawing the map of opportunity.

Three Scenarios for 2030:

1. The Great Rebalancing: Knowledge workers continue dispersing from superstar cities to mid-size metros and rural areas, reducing spatial inequality but challenging traditional agglomeration economies.

2. The Hybrid Equilibrium: A new steady state emerges with workers splitting time between urban offices and rural homes, creating vibrant “spoke” communities within a day’s drive of major hubs.

3. The Digital Divide Deepens: Places with poor digital infrastructure fall permanently behind, creating a new geography of haves and have-nots based on connectivity rather than proximity.

Our evidence—particularly the strong rural zoom town effects and persistent anti-zoom town patterns in expensive metros—suggests we’re heading toward Scenario 1, with profound implications for everything from infrastructure investment to school funding formulas.

The Lasting Legacy

When that software engineer traded her Mission District studio for mountain views, she joined millions in a grand reshuffling that our analysis confirms was systematic, not random. Pre-pandemic occupational structures—once a mere Census curiosity—became destiny. Counties that happened to have concentrations of managers, analysts, and creatives in 2019 found themselves winners in 2022.

This isn’t just about remote work. It’s about what economists call “spatial equilibrium”—the balance between wages, rents, and amenities that determines where people live. The pandemic didn’t just tip that balance; it knocked over the entire scale. Our fixed effects models, instrumental variables, and heterogeneity analyses all point to the same conclusion: the geography of opportunity has fundamentally changed.

The zoom town premium is real, measurable, and likely permanent. The places that captured it offer a preview of America’s next economic map—one where bytes matter more than proximity, and where a county’s greatest asset might be its bandwidth rather than its location.

This analysis was conducted using the American Community Survey 2019-2022 5-Year Estimates and Population Estimates Program data from the U.S. Census Bureau. All code and data are available for replication.

Analysis Summary: - Counties analyzed: 3,210 - Time period: 2019-2022 - Remote work-population growth correlation: 0.289 - Treatment effect: 2.32 percentage points - Top zoom town: Harding County , New Mexico